When Thirds Collide: The Seventh Sharp Nine Chord

Most guitarists have encountered some form of the 7#9 chord. It can be heard in The Beatles’ “Taxman,” Pink Floyd’s “Breathe,” Prince’s “Sexy MF,” as well as in songs by Stevie Ray Vaughan, Red Hot Chili Peppers, the Pixies, and many others. It is often referred to as the “Hendrix Chord” because it shows up in many Jimi Hendrix songs. (“Purple Haze,” “Spanish Castle Magic,” “Foxy Lady,” and “Crosstown Traffic”, are a few examples.)

But the 7#9 chord was used to great effect long before Jimi Hendrix included it in his own compositions. In jazz it popped up in pieces by Grant Green, Thelonius Monk, Charles Mingus, and notably in the Miles Davis modal masterpiece “All Blues,” where it appeared not once but twice, as a D7#9 and a D#7#9. Hendrix and Pink Floyd were both influenced by jazz that explored the 7#9 chord, an important reminder that the history of music is a continuum, and that musicians often assimilate their influences and revamp them to their own purposes. The 7#9 chord is a shining example of how influences not only transcend genre but often mutate into new forms of creativity.

The 7#9 chord voicing is a bit of conundrum, in that it mixes disparate aspects of key elements that makes the engine of Western music go: the third interval. How we approach the third interval is what gives music the major or minor feeling. (Major thirds create a happy/ triumphant feeling, and minor thirds, or flat 3rds, create a sad/ mysterious feeling.) The 7#9 chord mixes major and minor thirds, effectively creating an antinomy—the paradox of a happy/sad, nasty/ nice feeling.

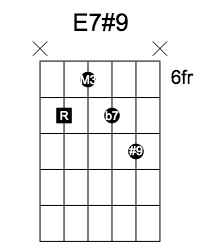

Let’s take the most commonly used 7#9 chord shape and dissect it using music theory in order to gain a deeper understanding of this most paradoxical of chords.

Example:1

Below are other examples of the 7#9 chord. All of the examples are in the key of E, and most are movable chord forms (with a few adjustments for open strings).

Example: 2

Example: 3

Example: 4

Examples 2 through 4 are open chord shapes played near the guitar nut. Depending on what sort of tone color you want, all of the above shapes will yield full, rich sounds perfect for a variety of styles. They work particularly well for solo or duo arrangements, as well as jazz, latin and classical, where low bass notes are desired. But none of these are hard and fast rules (and rules were made to be broken anyway), so let your ear be your guide.

Example 6 creates a modified triad (third, b7, #9) played high on the treble strings while adding the low E root on the 6th string. It is a hybrid of examples 3, 4, and 5. Of course one could simply omit the 6th string to get a 7#9 feeling, but keep in mind that there is no root note or fifth interval being played, so another instrument might need to play the E root.

Example:7

Example 7 moves the notes of example 6 up to the 6th fret, but keeps the low E note on the 6th string. It is essentially the “Hendrix Chord” without the 5th string. It is a good modification to use when trying to keep chords tight for syncopated playing or “stabs.” One could modify this shape and put the root high on the first string for a ringing open E note that is evocative of some disco or funk grooves.

In many circumstances it is totally reasonable (and in fact preferable) to use the strumming hand to select which notes in the chord you want to actually play. Hendrix, Stevie Ray Vaughan and many other skilled players were often selective in which notes within a chord they would let ring out at any given time. So while a player might choose to place his fretting hand in such a way that they can press down all of the notes in a chord, the strumming hand often selects which notes sound and which notes are dampened. The fretting hand can also play a part by selectively muting particular strings as needed.

Example: 8

Example 8 is the ubiquitous “Hendrix Chord.” It differs from example 1 in that it includes the open 6th string E note, which doubles the octave note (E) on the 5th string. It can be expanded by letting the high E ring out. Note that the open 6th and 1st strings only compliment this chord shape in the key of E. When moving these shapes around, players should omit the outside E notes on the 1st and 6th strings and stick with the notes on the interior strings. The root of this shape is on the 5th string for any key.

Example: 9

Examples 9 and 10 are chord voicing options with a 6th string root. The patterns are movable shapes that work well alongside similar 6th string root chord shapes, like minor 6th and minor 7th forms.

Example:10

Example 11 is a modification of example 3. However, because it is now being played with the root on the 12th fret of the 6th string. It is not using any open notes, and the 5th string is being muted. It is perhaps easiest to play this with the thumb on the 6th string, which will allow the 5th string to be dampened and made into a ghost note. Example 11 allows guitarists to play further up the neck.

Example: 11

In the often fractious, polarized modern world that we live in, where all too often people seem to want to view things as black and white and either/or, the 7#9 chords offer a middle way. It is a chord that we could conceivably philosophically carry over into the "real world." A chord that provides deeper understanding of the complexities of music and (perhaps) life in general. It is a chord that can function as an alternative to binary thinking, one that incorporates the best of both worlds into a glorious, funky unity. As musicians, and people, we can learn a lot from the 7#9 chord and its incorporation of opposites into a greater, more harmonious whole. The 7#9 chord invites the celebration and unification of opposites which can often yield possibilities that not only work well together, but can often work better together.

Comments

Post a Comment