Feeling The Sound

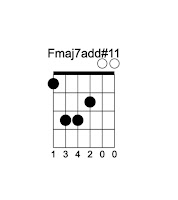

For years as a guitarist I had no idea what an Fmaj7 add#11 chord should be called. I just knew that when I played that particular chord shape, it sounded good and created a color or a feeling that I liked. The specific ring of the open high strings in combination with the fretted low notes created an inexorably pleasing and strange sound. I had little theoretical insight into the particulars of the chord. I just thought of it as being some bizarre form of F. But the exotic and complex feelings that this chord evoked in me were magical. Here is a diagram of the chord/ shape that I mean.

I don't exactly remember when the above chord shape became something I began to consciously play. I probably inadvertently played it in the frustrating process of learning the full barre chord shape -most likely because my first finger wasn't strong enough to hold down all of the strings. But somewhere along the line, I began to use this modified barre chord shape because I liked the way that it sounded and I began to use it in my own playing and songwriting. But I still didn't know that it was called an Fmaj7 add #11 -I still thought of it as some bizzaro F chord. The point is that I began with what sounded good to me. Essentially, I began with what I liked.

Beginning a relationship with an instrument is a very important time. It is when you (hopefully) begin to discover what it is that gets you excited about the instrument, what makes you want to discover more, dig deeper and spend more time with the instrument. Beginning the way that I did -mostly self-taught, with limited formal training and instruction- was a great way to begin playing guitar. It was sometimes frustrating, but that led me to work harder and eventually to deeper understanding. This is not to negate the value of things like music theory, notation, sight-reading, etc. But, from what Buddhists would call a “beginners mind” approach, names and rules of convention had little bearing on the actual feelings that the sounds from the instrument elicited on me. Although I've since learned many musical conventions and used them to help me be creative, they are still often merely a way to help me remember things, keep my thoughts straight and streamline the communication of an idea. I still rely on a strong sense of how I feel (or want to feel) music in my playing.

One of the most difficult things to write about, teach or explain about music is how to feel the sound. Obviously, you can physically feel the sound of music (a loud bass line or a kick drum, etc) and that is definitely a part of it. But what about the psychological aspects of "feeling sound" on an emotional level? Something that we can call emotional resonance. That is to say, a sense of emotional connectivity with the sound being played. How the music makes you feel. If one has never felt this it is difficult to explain, it must be felt and experienced on an individual level. Although I think most people have some sort of feeling about music. It can be largely subjective to the preferences and prejudices of different individuals. While some might love Black Flag, Willie Nelson, Mozart, Tupac or The Beatles, others might despise one (or all of) them. Musical taste is quite a varied thing, but it can also change over time and through experience.

There are different ways to feel music. Perhaps the most easy way is simply through active listening. Which could be defined as being present to specific sounds and how they make a person feel emotionally. Another way to feel music is via the body. Dancing is the most obvious example of this. Musicians have to refine this dynamic through the development of physical and mental abilities in relation to time, melody and harmony, but also this dynamic needs to incorporate emotion. This means practice. Practice to the extent that “muscle memory” in relation to rhythm develops, but also practice to build the ability to find a "groove" and stay in it. "Finding the pocket," "swinging," "stretching out," are all common ways to say this amongst musicians. This skill is where some of the emotional element resides. There is more to the equation than just listening, memorization and practice. There is a synthesis of myriad aspects that has to happen. A synthesis of the physical and listening aspects of our experience of music and the emotional resonance therein. This means being present. Which brings us in a circle back to the "beginners mind" concept. Listening with new ears. There needs to be the ability to “tune in” to the present moment and actualize the emotional depth of the performance through direct physical and mental means, both intuitively and through experience. On a basic physical level this can often be achieved by finding a sense of the beat with the body; tapping one or both feet, nodding the head, swaying in time -or a combination of all of the above helps to ground performance in actual somatic experience so that one can “lock-in” to the groove of the song and allow that physical rhythmic anchoring to adjust to and help propel the performance.

On a tactile level, how we literally feel or touch the sounds that come out of our instruments can have a great bearing on what it is that comes through to the listener. The adage “tone is in the hands” is, to a great extent, true. A masterful player should be able to make anything sound good. From the cheap pawn shop guitar with a warped neck, to a pristine Gibson Les Paul, an emotional player should be able to create something that sounds good -or at least interesting. In other words, the best with what is. A stick and a piece of wire should be sufficient to create something if the studied performer has the right head-space and is present and listening.

This is not to say that sight-reading or more academic ways of playing music are invalid. Not at all. They certainly have a place and a time. But it seems to me that getting”off of the page” helps free up the mind and body to focus more intently on listening more deeply rather than prioritizing other senses like the eyes. Indeed, speaking from personal experience, the mental space of reading music, rather than playing by memory or improvising, has a different feeling. Just like recording and mixing music on a computer or a tape machine is different. You're looking more than your listening. I recently mixed a record of instrumentals partly on an analog mixing desk with no computer in front of me -just faders- and it was a noticeably different experience than sitting in front of computer screen looking at the waveforms. Simply closing ones eyes and listening seems to always make music become more heightened. It prioritizes the ears over the other senses.

A form of limited thinking can come from academic music. Or maybe to put it more specifically, a kind of categorical compartmentalization can limit a musician. For example: a relative of mine received a PhD in music performance and they can play anything that is put in front of them on the piano. They're a masterful and skilled musician in their own right. But I once asked if they ever improvise or compose? They said: “I can’t, I never learned how.” They're capable of playing the most intricate and difficult pieces on piano, but have a limited sense of creative improvisation. The process of deep study they underwent did not help to develop inherent compositional creativity, they became stuck on the page. Which has a lot to do with the category of degree that they pursed and the difficulty of learning the classical method for piano -which is no small feat in itself. Still, they can evoke such emotion as a player -albeit interpreting other people's work- that it would be impossible to say that they didn't learn how to feel music. Another instance is my mother, she learned to play classical piano as a child and grew up sight-reading. While she can play advanced Chopin, Rachmaninoff, Mozart, etc, she can’t easily improvise and often has a hard time finding a groove if she doesn’t have sheet music in front of her. But does she feel the music any less that she can play?

So, this is not to infer that approaching from a "learned by ear" approach is not without its own limitations too. The Fmaj7 add #11 chord, that we looked at above, offered me an opportunity to understand what some of the limitations of self-erudition are. When writing songs while I was growing up, I would often ponder what to call this particular chord. At first, this was due to the fact that I had a limited knowledge of music theory and, so called, compound intervals were fuzzy at best. As time went on, and I was able to decode chords based on the placement of the intervals, I began to ask myself more fundamental questions. What if F wasn't the root? What would I call it then? If C was the root, was it actually a Cmaj7 add11, 13? Or if A was the root, was it now an Am9 b6 chord? Additionally, I knew this chord as a shape and a sonic feeling more than anything else, and I would often move the shape up or down the neck so that it would create variations of the F#, G or A chords -a trick I had often heard Daniel Ash, Robert Smith and Dave Navarro employ. But what was I to call all of those chords too? The chimerical nature of the way that music seemed to morph and shift to my perspective was both exciting and bewildering. I felt constrained by my lack of knowledge. I needed some theory to ground my intuitive musical abilities. But I still felt the music emotionally too.

The whole premise of this line of thinking is obviously subjective and hypothetical (not everybody learns the same) but I often wonder about training kids to sight-read at an early age without introducing improvisation and a deep sense of rhythm and groove through things like Eurhythmy or dance. Perhaps the Suzuki method helps assuage this? I hypothesize that not encouraging deep listening prioritizes the brain to "see" music rather than "hear" music. Because the ears are the only sense organ that is directly wired into the limbic system, it stands to reason that if we prioritize listening, we may "feel" the music better. I would go one step further with this line of thinking, if we feel music better, we can improvise more skillfully.

I largely learned guitar/ music through self-erudition, which meant listening to tapes, CD's and records and picking out parts by ear, I also learned a lot playing with other musicians, jamming and exploring other peoples music out of songbooks, jazz charts, etc. I had some great teachers in school and took a few private lessons in my early teens. But I mostly developed as a musician autonomously via an enormous appetite for all kinds of music and through social interaction. While I played some piano and saxophone as a child, I had difficulty doing the multitasking necessary to sightread quickly and so it was always a struggle. I actively avoided sight-reading as much as possible until I was in my late 20’s and literally forced myself to do it as much as possible until I had the open and first positions memorized. This still took me 4-5 years of practice but it ultimately was worth it. I am a more well-rounded musician now and can straddle the fence between both worlds pretty well. But it is something that wanes easily and if I don’t practice sight reading for a few months it starts to slip and gets rusty. Especially in regard to rhythm. In my experience there is something so odd about reading musical rhythms off a page. Because you are basically looking forward to the next note, just ahead of the note your hands are playing and your ears are hearing. So there’s something not quite fully present about the process for me. On the other hand, there is a “flow state” that can occur with advanced sight-readers. A college educated guitarist I know once told me that sight-reading was one of the only ways he could turn his mind off and just be present. So it likely varies based on the person and the skill level.

Even when I was 10 or so, learning to play saxophone, the most fun I had was to put on blues cassettes and play along to them freely. The songs we were learning in band class like “When The Saints Come Marching In” were drudgery compared to the excitement and fun I had just blowing free along to my parents tapes. That ability carried over to my initial forays into the guitar. I would put tapes and CD's on and just try and solo -regardless of key. I had a Mel Bay book and some Guns N' Roses and Doors songbooks that I began to learn chords from, but what seemed most exciting, most emotionally resonant, was to try and connect with things in a present improvisational way. I had learned an important lesson early on, that “feeling” the music was what made it most enjoyable for me. However, as I developed as a musician I began to to return to the basics and I began to incorporate the academic ("seeing") approach more. What ended up happening was that I developed a larger vocabulary and a deeper understanding of what it was that I felt I liked and why.

After 30 years of playing guitar I came to a place of equilibrium. A place where I can balance the polarities of being an "ear" based musician and an "eye" based musician. But one thing that hasn't changed is that I still rely on intuition to feel the music. That is something that almost always functions as way to move forward and find a way to be creative. That was my journey. Does that invalidate approaching things from the opposite way? Hardly, but what is crucial -no matter which way you approach things- is finding a way into the emotional heart of things. If that isn't happening in your process as a musician you need to find a way to make it happen, because it is the only way to make your music really communicate to others. In the modern era of digital recording, with all it's attendant tools that can auto-tune, beat-map, quantize or tweak most anything, I worry that people are losing the ability to connect to emotion. Perhaps prioritizing feel over perfection is a way forward?

Because I spent so much time following my gut and trusting the emotion of what I heard or played, I can now effectively straddle the fence between two different ways of operating. But the value of trusting one's emotional instincts as a musician is a lesson I have tried to remember throughout my career/ life as a musician. It is almost always the truest representation of something that will work. If it feels good, it is good -regardless of how you got there.

Comments

Post a Comment